Epidemiology

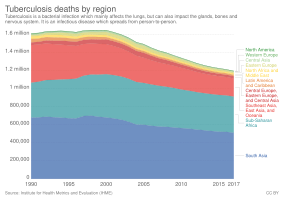

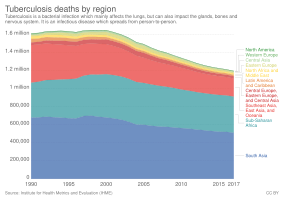

Roughly one-quarter of the world's population has been infected with M. tuberculosis, with new infections occurring in about 1% of the population each year. However, most infections with M. tuberculosis do not cause TB disease, and 90–95% of infections remain asymptomatic. In 2012, an estimated 8.6 million chronic cases were active. In 2010, 8.8 million new cases of TB were diagnosed, and 1.20–1.45 million deaths occurred (most of these occurring in developing countries). Of these, about 0.35 million occur in those also infected with HIV. In 2018, tuberculosis was the leading cause of death worldwide from a single infectious agent. The total number of tuberculosis cases has been decreasing since 2005, while new cases have decreased since 2002.

Tuberculosis incidence is seasonal, with peaks occurring every spring/summer. The reasons for this are unclear, but may be related to vitamin D deficiency during the winter. There are also studies linking Tuberculosis to different weather conditions like low temperature, low humidity and low rainfall. It has also been suggested that Tuberculosis incidence rates may be connected to climate change.

At-risk groups

Tuberculosis is closely linked to both overcrowding and malnutrition, making it one of the principal diseases of poverty. Those at high risk thus include: people who inject illicit drugs, inhabitants and employees of locales where vulnerable people gather (e.g. prisons and homeless shelters), medically underprivileged and resource-poor communities, high-risk ethnic minorities, children in close contact with high-risk category patients, and health-care providers serving these patients.

The rate of TB varies with age. In Africa, it primarily affects adolescents and young adults. However, in countries where incidence rates have declined dramatically (such as the United States), TB is mainly a disease of older people and the immunocompromised (risk factors are listed above). Worldwide, 22 "high-burden" states or countries together experience 80% of cases as well as 83% of deaths.

In Canada and Australia, tuberculosis is many times more common among the aboriginal peoples, especially in remote areas. Factors contributing to this include higher prevalence of predisposing health conditions and behaviours, and overcrowding and poverty. In some Canadian aboriginal groups, genetic susceptibility may play a role.

Socioeconomic status (SES) strongly affects TB risk. People of low SES are both more likely to contract TB and to be more severely affected by the disease. Those with low SES are more likely to be affected by risk factors for developing TB (e.g. malnutrition, indoor air pollution, HIV co-infection, etc.), and are additionally more likely to be exposed to crowded and poorly ventilated spaces. Inadequate healthcare also means that people with active disease who facilitate spread are not diagnosed and treated promptly; sick people thus remain in the infectious state and (continue to) spread the infection.

Geographical epidemiology

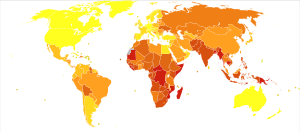

The distribution of tuberculosis is not uniform across the globe; about 80% of the population in many African, Caribbean, south Asian, and eastern European countries test positive in tuberculin tests, while only 5–10% of the U.S. population test positive. Tuberculosis is more common in developing countries; about 80% of the population in many Asian and African countries test positive in tuberculin tests, while only 5–10% of the US population test positive. Hopes of totally controlling the disease have been dramatically dampened because of a number of factors, including the difficulty of developing an effective vaccine, the expensive and time-consuming diagnostic process, the necessity of many months of treatment, the increase in HIV-associated tuberculosis, and the emergence of drug-resistant cases in the 1980s.

In developed countries, tuberculosis is less common and is found mainly in urban areas. In Europe, deaths from TB fell from 500 out of 100,000 in 1850 to 50 out of 100,000 by 1950. Improvements in public health were reducing tuberculosis even before the arrival of antibiotics, although the disease remained a significant threat to public health, such that when the Medical Research Council was formed in Britain in 1913 its initial focus was tuberculosis research.

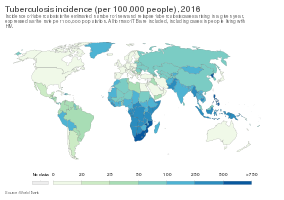

In 2010, rates per 100,000 people in different areas of the world were: globally 178, Africa 332, the Americas 36, Eastern Mediterranean 173, Europe 63, Southeast Asia 278, and Western Pacific 139.

Russia

Russia has achieved particularly dramatic progress with decline in its TB mortality rate—from 61.9 per 100,000 in 1965 to 2.7 per 100,000 in 1993; however, mortality rate increased to 24 per 100,000 in 2005 and then recoiled to 11 per 100,000 by 2015.

China

China has achieved particularly dramatic progress, with about an 80% reduction in its TB mortality rate between 1990 and 2010. The number of new cases has declined by 17% between 2004 and 2014.

Africa

In 2007, the country with the highest estimated incidence rate of TB was Eswatini, with 1,200 cases per 100,000 people. In 2017, the country with the highest estimated incidence rate as a % of the population was Lesotho, with 665 cases per 100,000 people.

India

As of 2017, India had the largest total incidence, with an estimated 2 740 000 cases. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2000–2015, India's estimated mortality rate dropped from 55 to 36 per 100 000 population per year with estimated 480 thousand people died of TB in 2015.

North America

In the United States Native Americans have a fivefold greater mortality from TB, and racial and ethnic minorities accounted for 84% of all reported TB cases.

In the United States, the overall tuberculosis case rate was 3 per 100,000 persons in 2017. In Canada, tuberculosis is still endemic in some rural areas.

Western Europe

In 2017, in the United Kingdom, the national average was 9 per 100,000 and the highest incidence rates in Western Europe were 20 per 100,000 in Portugal.

Number of new cases of tuberculosis per 100,000 people in 2016.

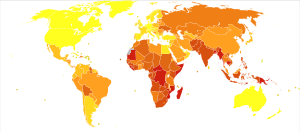

Tuberculosis deaths per million persons in 2012

Tuberculosis deaths by region, 1990 to 2017.

Comments

Post a Comment